-------------

|

| Outer line of Confederate fortifcations, in front of Petersburg, Va., captured by 18th Army Corps, June 15, 1864. Library of Congress. |

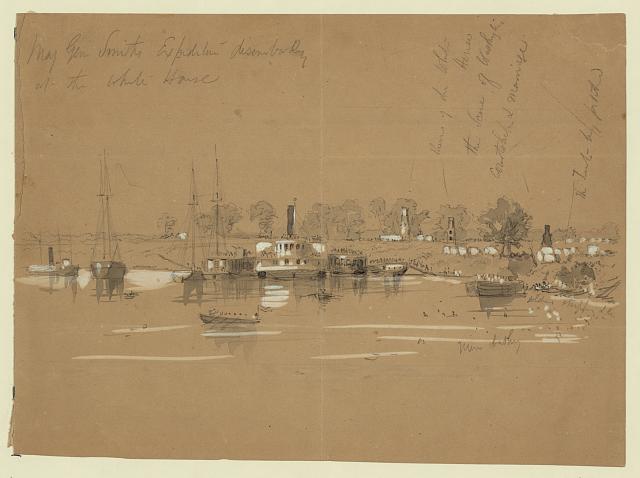

...and finished my morning report. Thos. Pringle, who is with the cooks, brought the coffee up very early. After breakfast I commenced writing a letter, but before I finished it we received orders to pack rifles and be ready to march immediately. We left at 10 a.m., our regt. in the lead, and arrived at the White House at 3 p.m. We halted on the other side of the R.R. from where we encamped before and stacked arms and the cooks made coffee. I took a good wash before supper.Hoster didn't know it, but Ulysses S. Grant's great turning movement that would carry the Army of the Potomac across the James River to confront Petersburg had just begun.

Monday, June 13thMaj. Gen. William F. Smith's 18th Corps had barely returned to the Army of the James when Smith received orders to depart early on the morning of June 15th to cross the Appomattox River and attack Petersburg. At 2 a.m., the column moved out.

Very warm. I sent Parmalee after a ration of beans and Parmalee cooked them during the night and we had them for breakfast this morning. We also drew a few potatoes this morning, and Parmalee made some potato soup for dinner. Our sutler came up this forenoon and sold any amount of goods. I purchased a can of peaches, a can of oysters, a jar of pickles, some cake and cheese and with some coffee that Wade made, he and I had a fine dinner. Gen. Martindale came over and took breakfast with Col. Guion at his solicitation. The Gen. ate his breakfast under a large tree. Wade and I put up our shelter tents on our guns and lounged in the shade all afternoon. We had to leave at 6 o'clock and march to the landing a few hundred yards in the distance where we embarked on the transport "Webster" about dark. I took a quiet evening smoke, after which I turned into my nest, a small space in the cabin on the upper deck which I had reserved. Our regt. is all aboard.

Tuesday, June 14th

Warm and pleasant. We lay in the stream last night and started at 4 o'clock this morning, passing West Point at 7. Our cooks made coffee this morning. Corpl. Wade is now my chum. Passed Yorktown at 9:30 a.m., passed Ft. Monroe at 12:15, Jamestown at 4:30 p.m., Wilson's Landing at 5:50 p.m., and arrived at Bermuda Hundred at 7:30 p.m. At half past eight we took up our line of march, marching to near where we crossed the Appomattox at pontoon bridge and stopped for the night.

Wednesday, June 15thThe 148th and the rest of Brig. Gen. John H. Martindale's were third in line to cross the river on this morning. Traveling with the column, New York Times Correspondent Henry J. Winser painted the scene for his readers:

Very warm. We started out very early this morning, crossing the Appommattox on a pontoon bridge...

With springy, elastic step MARTINDALE's well-tried veterans passed over, conversing gayly as they came, and bringing with them a spirit that entirely dispelled the grave and sober spell which the silent movement of their comrades had thrown over all. With the sun came warmth, and we lookers-on on the river bank stopped shivering and became hopeful of getting to Petersburgh before night.The 18th Corps approached the city from the northeast. Martindale's division advanced on the Appomattox River Road, while Smith's other two divisions and his cavalry moved on Martindale's left. Early that morning Brig. Gen. Edward W. Hinck's all-black division engaged and defeated a small Confederate force. After this success, Smith took the better part of the day to scout, organize, and close his forces up upon the Confederate defensive line. In the meantime, the 148th New York occupied the right flank of Martindale's advance. John L. Hoster's account countinues:

...when we came to a house where lived a woman who professed to be Union, the skirmishing commenced. We proceeded a short distance when nearly all of our regt. was sent on skirmish, the right of our company on the Appomattox. We ran into the enemy line before we were aware of it. They fired a volley into us. We concealed ourselves as much as possible and during the day we dug small rifle pits for protection. Soon after noon I fired on a man across the river who was taking observations with a glass. He ducked his head and went off around a hill and a battery soon made its appearance and began to throw shot and shell at us, wounding James Roe and Chas. Marshall, H Co. Benjamin Watkins in command of our right fell back offering the rebs an opportunity to flank us. At 4:30 we were obliged to surrender to a company of the 26th. Va.Further details of the capture can be found in a letter sent to the Seneca County Courier by Chaplain Ferris Scott:

...the saddest part of the tale for Seneca Falls remains to be told. Lieut. Court. Van Renssalear, as brave and fine an officer as we have in the Regiment, had the misfortune of being captured by the Rebs, together with some 25 or 30 of his Company. He and those captured with him were on the extreme right of the Regiment and had taken possession of a house as a shelter from which to act as sharp-shooters. While in the house the Regiment was ordered to fall back. He did not get the order, and was left behind; and before he was aware of it, the Rebs surrounded the house and took the whole squad prisoners. I haven't been able to obtain an accurate list of those taken yet, but will in a day or two, and will send it on. Sergt. Hoster, John Hudson , and in fact the majority of the good fighting men in the Co., are gone to Richmond. The only ones who escaped were those who had been sent to rear for ammunition, water, &c., &c., and who were not in the fight at the time.Sergeant Hoster did not in fact go to Richmond, as Scott believed. Hoster continued to record his own account:

We were marched back to their breastworks and sent by the Major in command to the Col. commanding Battery 5. From there to Gen. Wise and to the Custom House in Petersburg where we were questioned, then to P.M. office where we were searched and relieved of our watches, letter knives, etc. My spy glasses were also taken. We were then confined to a building on a back street. There we found Thos. Crelly of our company, who had arrived before us.For the Confederates attempting to make sense of Grant's latest move, these prisoners from the 148th New York provided some valuable information. With a quick search at the excellent Siege of Petersburg Online blog I found this bit of information published in the June 16th edition of The Petersburg Express:

Twenty-three prisoners brought in last night, belonging chiefly to the 148th N. Y. regiment, all concur in the statement that Baldy Smith’s entire Army Corps (the 18th) is on this side of the river again.Smith and his 18th Corps succeeded in capturing Petersburg's outer works on the evening of June 15th, but they lost a golden opportunity to take the city quickly. For John L. Hoster, his great ordeal as a prisoner of war was just beginning.